Are Sports Prepared to Deal with Mental Wellness of Athletes?

Modern Athletes: Human Beings or Mortal Engines?

The December Newsletter is lengthy due to the extensive research on the topic and personal reflection on suicide and potential influences and impacts. It is however absolutely imperative at this time because people, in general, are dealing with an abundance and overwhelming mental-health issues not only in North America but also globally due to COVID-19. Coaches need to be extremely concerned because athletes at all levels are already or will be affected. A large part of this Newsletter also centers on Michael Phelps and other Olympians and their mental torment as Olympic athletes.

Society seems to hold the belief that athletes possess immense physical prowess and extreme mental toughness when dealing with the pressure of training and competition. And… therefore they have to be better equipped to handle and withstand more stress than the average person. Researchers point to the fact that exercise produces a moderate clinical effect in the treatment of depression – society, therefore, believes that those who train more vigorously handle stress and anxiety better. Really? However, that is a big fallacy and myth! Here is the latest disturbing News: Another elite athlete (swimmer) is lost at the University of Michigan, Ian Miskelley, committed suicide on September 17, 2020 (See below for letter by his father) while two female High School Volleyball players died on September 21 and October 4, 2020, respectively.

Although suicides among professional athletes were reported as early as 1940 the topic of mental health issues has not been exactly a priority topic with sport federations, coaches, or presentations at Sport conferences. Subsequently, there has been relatively little research on the mental health and psychological well-being of elite athletes. However, mental health issues seemingly are taken more seriously, especially after former Olympians, including Michael Phelps, have come forward in the recent HBO Sports documentary: “The Weight of Gold” to share their stories.

One of my favourite poems by Robert Frost has been the guiding light throughout my teaching/coaching career… And I have followed its path ever since!

…Two roads diverged in a wood, and

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference…(partial)

To develop the discussion, I backtrack to a provoking presentation delivered on December 1, 1994, at the Annual Athlete Award Celebration in Landshut, Bavaria.

…Sports Today – Joy and Enjoyment or Fron and Paradox?

…Sport is No longer Sport…

…When detrimental to physical or mental health or leads to death…

Trained in classical philosophy at “Humanistisches Gymnasium” (Prep-High School for Humanities) I firmly believe that “sound mind – sound body” is not just a slogan in Greek philosophy but was indeed a way of life in that society. And… English philosopher and physician John Locke (1632-1704), one of the most influential thinkers of the Enlightenment period, reinforced the very same concept, which by the way became the slogan for modern physical education.

Wow! Was I ahead of the time?! I presented the topic at several Congresses during the 1990s and was subsequently labeled, “nuts, crazy, and weird” …and called other expressions by coaches (especially males) because I dared to link physical and technical development to the mental state, health and wellness of athletes. Despite their verbal abuse at that time, ‘I kept on trucking’ because I always believed that the truth about the abysmal occurrence of mental health issues within sports would surface sooner or later!

Actually, listening at the Annual ASCA World Swimming Clinics to the self-proclamation of Olympic swim coaches I wanted to get up and leave because younger coaches in the audience were ‘gaga’ over such success, and eager to follow in their footsteps, although without the education or the necessary tools to deal with mental health issues affecting modern athletes. Tell me, just how would a Novice coach manage that?

‘Fron and Paradox’ of Sport

The Fron: According to the dictionary can be interpreted as: labour, drudgery, slave labour or forced labour (!), burden, load, yoke, bondage, crux, and plague. Could we apply that to modern sport and the present status of athletes suffering under real or perceived pressures, such as

Having to train 365 days per year

Having to develop patience when dealing with training and performance difficulties

Having to deal with the slowdown or decrease of performance

Having to develop self-awareness and then nurture it

Having to learn to make correct decisions at the right time

Having to depend on team or teammates

Having to forgo free or private leisure time because sport has replaced it

Having to give up family connections, friends and social time

Having to delay education, studies or vocational training

Anguishing over losing control and overview over one’s situation or position

Having to face and continue to battle with the ‘Self ‘as agon’ (contest, struggle) becomes personal agony

The Paradox:

Philosophically, the term ‘sport’ is derived from Latin ‘disportare’ = to carry away … from the daily grind or work [!] … It is also linked to ‘amateur’ = lover, friend, in essence, ‘lover/friend’ of sport. This should cause us to reflect on the meaning of present day sport!

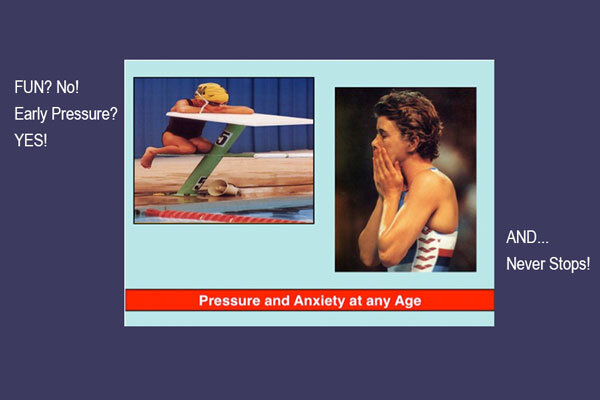

When 73% of children and youth at age 12-13 years drop out of sports due to pressure from coaches and/or parents

When leading athletes like Michael Jordan (NBA) and Wayne Gretzky (NHL) declare: “I am quitting because playing is no longer FUN”

When friends and family are neglected over the pursuit of sport as it becomes all-consuming

When the Olympic “altius, citius, fortius (faster, higher, stronger) becomes a personal addiction, a mania, potentially resulting in drug use or doping, and possibly leading to death

When human bodies are transformed into ‘high tech machines’, chemically enhanced, misused, abused, or wasted

When athletes have to decide under pressure whether to compete under the ‘fair play’ rules or cheat with drugs or doping’ because of the ‘win at all cost’ attitude

When drug use becomes acceptable because Ben Johnson (1988 Canadian Sprinter) just was ‘stupid enough’ to get caught

When drug use and doping become acceptable because ‘winning is everything and losing is death’

When athletes are doped, and become ‘human performance’ machines without regard for their health or die later (US sprinter Florence Griffith Joyner at age 38 due to heart failure)

When female athletes are forced to become pregnant, then abort to maintain higher levels of hormones to enhance their competition success

When former female athletes experience miss-carriages in their post-sport lives due to lengthy doping during their careers

When a soccer player is shot because he put the ball into his own net

The Modern Tragedy in Sports

Olympic Athletes Dying: Document about Suicide among Olympians

HBO released a sobering sport documentary on July 29, 2020, telling about the experiences of Olympic athletes, pressures, and anxiety. Michael Phelps as the narrator and the world’s greatest athletes discusses mental health struggles in sobering stories about depression, suicidal thoughts and discloses actual suicides of befriended athletes. The film comes at a time when COVID-19 has postponed the 2020 Olympic games – the first time ever in Olympic history – and has greatly intensified mental health issues among athletes. The Washington Post and CNN have taken up the pursuit of suicide stories among teens and athletes at all levels. However, I have yet to see such attempts by Canadian Media or Networks.

The Associated Press

Brett Rapkin, Director

Posted: Aug 4, 2020

Modified by Schloder

Olympians Michael Phelps, Apolo Anton Ohno, Jeremy Bloom, Shaun White, Lolo Jones, and Sasha Cohen open up about their mental health struggles and challenges about depression and suicide. They’re calling out a system that has allowed the problem to become – as Phelps put it “an epidemic,” and are sharing their pain for the first time in “The Weight of Gold.” The documentary aims to expose current problems and tries to incite changes in Olympic leadership to help others experiencing similar issues and their feeling of being left alone. They describe a culture of silence and a lack of mental health resources within their specific sports and at the highest levels of the Olympic games. Phelps, the most decorated Olympian of all time, doesn’t think the leadership on Team USA or the International Olympic Committee cared about him outside of his athletic performance. The document discloses a number of suicides among Olympians, including aerial skier Jeret “Speedy” Peterson, sports shooter Stephen Scherer, cyclist Kelly Catlin, and bobsledder Steven Holcomb.

Speaking from his home in Los Angeles, Apolo Ohno told The Associated Press that,

…In an ideal world, every time the International Olympic Committee gets a sponsor, it would dedicate a portion of the resulting funds to mental health resources. That seems like a no-brainer to me. If I was the CEO of X Company, which is a global company, and you were gonna tell me as a part of these sponsorship dollars, some of that money is going to go towards these resources, I would be ecstatic. That’s the type of organization that I want to partner with. And I believe that the conversation like this documentary is going to push that narrative along…

Ohno won two gold, two silver, and two bronze medals. He thinks the United States Olympic and Paralympic Committee are taking necessary steps – albeit slow – because they’re a large organization. He believes that it needs to come from the IOC level, and a real conversation that’s authentic, not politically driven, should engage in dialogues to help Olympic champions because they represent what human beings aspire to be.

In a statement to The Associated Press, the IOC said it “recognizes the seriousness of the topic” and had assembled a team of international experts in 2018 to review the scientific literature on mental health issues among elite athletes, resulting in a mental health working group. According to the Committee, the topic was discussed more openly at forums and panels in recent years, and that the IOC has launched a series of Webinars to help athletes cope with COVID-19, among other initiatives. Really? (Schloder: another slow operating bureaucratic committee as usual). Accordingly, “The IOC Athletes’ Commission will continue to work closely with the Mental Health Working Group on creating more resources as well as a helpline.” Jeremy Bloom, Olympian, and three-time world champion skier said recent efforts are “not going to solve all the problems overnight but it is a step in the right direction.”

Brett Rapkin, director of “The Weight of Gold,” hopes the documentary leads to better resources for Olympians. “They have this incredibly unique psychological journey they go on and it needs to be paired with appropriate resources to handle it.”

Featured Athletes:

Michael Phelps (born 1985) – most successful and most decorated Olympian of all times with a total of 28 swimming medals; all-time records for Olympic gold medals in individual and team events; suffered anxiety and depression; had suicidal thoughts; charged with drunken driving; experimented with marijuana; spoke at a Conference in 2018 about his depression: “I am extremely thankful that I did not take my life”

Apolo Anton Ohno (born 1982) – short track speed skater; eight-time medalist in the Winter Games; most decorated American Olympian at the Winter Games

Katie Uhlaender (born 1984) – skeleton racer; after wondering why she hadn’t heard from her close friend bobsledder Steve Holcomb in a couple of days, broke into his room, and found him dead in the Olympic Training Center in Lake Placid, NY; being treated by bureaucrats like a ‘leper’ when she suffered from panic attacks in 2018 after finding him dead of an overdose

Jeremy Bloom (born 1982) – Only athlete in history to ski in the Olympics and get drafted in the NFL; three-time world champion, two-time Olympian, and 11-time World Cup gold medalist; youngest freestyle skier in history to be inducted into the United States Skiing Hall of Fame in 2013

Sarah Cohen (born 1984) – 2006 Olympic silver medalist, three-time World Championship medalist, 2003 Grand Prix Final Champion, 2006 U.S. Champion

Shaun White (born 1986) – Professional snowboarder, skateboarder and musician; three-time Olympic gold medalist; holds record for most X-Games gold medals and most Olympic gold medals by a snowboarder; won 10 ESPY Awards

Bode Miller (born 1977) – former World Cup alpine ski racer; Olympic and World Championship gold medalist; two-time overall World Cup champion in 2005 and 2008; most successful male American alpine ski racer of all time

David Boudia (born 1989) – diver; won gold medal in 10 metre platform diving at the 2012 Summer Olympics; bronze medal in the same event at the 2016 Summer Olympics

Jonathan Cheever (born 1985) – snowboarder on the U.S. Snowboarding's SBX A Team; named the U.S. snowboarding champion in 2011; second American male ever in his discipline to win the World Cup; two World Cup 2nd-place finishes in 2011; ranked third in the World in snowboard cross (SBX).

Lolo Jones (born 1982) – Hurdler and bobsledder, who specialized in the 60-meter and 100-meter hurdles (2008 Olympic games); won three NCAA titles and garnered 11 All-American honours at Louisiana State University

Jeret ‘Speedy’ Peterson (1981-2011)… See under Suicide

…And What They Said…

Life has a narrow focus

There are no outside interests

Driven by fear of failure, and that someone on the other side is better; feeling pressure to find a better way to win

Seconds dictate whether Gold or Not

Shocked and devastated to fall in front of the world – dramatic experience

The guy in 4th place just disappears

Family image tarnished if a failure

No one to help you through that

Whole world built around you has crashed

What about after sport? Education? Family?

Olympic athlete – not sure if there is anything else

People see you as an athlete and nothing else

A new dude is waiting – hurts emotional stability

They extract the best performance from you – go back to the drawing board –find the best athlete again – it starts all over again – time after time to get the latest and the greatest

Pressure to perform takes a lot out of your health

My father is dying of cancer – I am not allowed to go home to be with him because they tell me that I am the only one (female skeleton slider), and they are counting on me

What do you have to show for?

Life is unbearable – stuck in a rot

Most days crying – don’t want to be alive

I ended up doing crazy things

I drove to get myself killed – confident to commit suicide – driving so fast to wrap myself around a telephone pole

Gold medal – Me and God in the bedroom (before suicide)

They are just engulfed in a system that has existed in a certain way for a very long time (about sports bureaucrats)

Olympic Athletes and Suicide

It is extremely disturbing, given the current age of these individual athletes coming forward now and disclosing themselves after so many years in this documentary, their anxiety, depression, suicidal thoughts, and stories about athletes and friends, who committed suicide. The burden throughout these years had to be tremendous, especially when no help was provided. Bobsledder Steven Holcomb realized this when he became aware his friend and fellow Olympian Jeret Peterson (aerial skier) had called 911 before committing suicide by gunshot in 2017.

Jeret ‘Speedy’ Peterson (1981-2011) – American World Cup Freestyle aerialist from Boise, Idaho; three-time Olympian, silver medalist at the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver; sexually abused by a roommate; battled depression after he watched in horror as a friend committed suicide in front of him in 2005; passed away from a self-inflicted gunshot wound near Salt Lake City on July 25, 2011

Steven Holcomb (1980-2017) – bobsled; long-time U.S. bobsledding star; drove to three Olympic medals after beating a disease that nearly robbed him of his eyesight; was found dead in Lake Placid, New York, May 17, 2017; had prescription sleeping pills and alcohol in his system; led the four-man US bobsled team to a gold-medal victory, ending a 62-year gold medal drought in the United States Olympic four-man bobsled competition; qualified for the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, in both the two-man and four-man bobsled

Pavel Jovanovich (1977-2020) – a member of 2006 Olympic bobsled team; second bobsledder to have died in the past 3 years after Holcomb; bronze medal at the 2004 world championships; died by suicide at age 43

Stephen Scherer (1989-2010) – US Cadet with the class of 2011 at the United States Military Academy; competed in the 2008 Olympic games in 10 metre air rifle; was only 19 and still a freshman at West Point when he qualified for the Beijing Games; transferred to Texas Christian University after leaving West Point; was found dead on October 3, 2010, in his off-campus apartment; cause of death was ruled to be a self-inflicted gunshot wound

Kelly Catlin (1995-2019) – pursuit racing cyclist; silver medal at the 2016 Olympic games; 3 consecutive World championships between 2016-2018; pursued a graduate degree in computational and mathematical engineering, musician, spoke fluent Chinese; described her struggle to balance school and cycling; suffered some crashes later in her career, breaking her arm and sustaining a concussion on a slick road; didn't remember that she had hit her head and mainly noticed her road rash abrasions; the concussion changed her, family members say but we only knew about her headaches; attempted suicide because she was frustrated; "she told me she hated failing the suicide attempt,” her brother said; suicide attempt left her with lung and heart issues; family and coaches persuaded her to rest; withdrew from the 2019 Track Cycling World Championships; "she had carefully planned it out and wrote an email hours before she scheduled her suicide; we got it and thought it was a joke, called the police; Catlin died in her dorm at Stanford University; an abrupt end to the 23-year-old's accolade-filled life – “she could do it all until it became too much,” they said

More suicides by athletes are recorded each year as progressively more mental-health issues are exposed. Sports Federations and coaches seemingly have failed to deal with athletes’ mental-health issues, and intervention is absolutely essential as athletes training for the 2020 Olympic games are now forced to refocus on the postponed 2021 Games.

Michael Phelps: Long-term Dilemma and His Struggles

One has to understand that competitive swimming actually is very boring. I should know as I trained for many years at the elite level. Circle swimming, following behind someone’s feet or butt, keeping an appropriate distance, and trying to stay motivated is not very exciting! Finishing a tough swim set, resting for a short period, followed by more repeats and repeats…and more repeats …in the same pattern! I used to rehearse my Mozart Cello pieces in my mind, humming along, and then forget what lap count I was on, which got me into real trouble! What saved me was my other sport training in Track & Field. Germans call it ‘Ausgleichs’ sport [balance, equalizer, compensation!].

Although swimmers are said to be very disciplined and also perform well in school, according to research, they tend to be perfectionists. On the other hand, many engage in rowdy behaviour, including getting drunk, smoking pot (I had seen it all as Assistant coach with the University Varsity team but as the saying goes … ‘boys will be boys’… declared our male Head coach!). One incidence resulted in smashing chairs through the hotel windows in Vancouver, BC after winning the Western Regionals resulting in 4000-dollar damage… and the Athletic Director at that time blamed me for such behaviour!

I remember very specifically, just months after the 2004 Olympics, Phelps took his celebrations too far when he was arrested for drinking underage and driving under the influence in his native Maryland. He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 18 months of probation. I sent an email to ASCA …Oh Boy! Did I ever get a tongue lashing via hateful emails because I dared to suggest that someone needed to deal with his situation or it might become habitual. Phelps’s success in swimming continued as did his behaviour … in fact, it got worse… and seemingly there was a cover-up by USA Swimming and the Sports Media.

Phelps’ primary swim coach Bob Bowman started to train him when he was about 7 years old and supposedly served as a ‘father’ figure, according to Phelps’s mother since the parents divorced. Bowman became the Head swim coach at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbour and enrolled Phelps in classes. Although he began studying sports marketing and management, he did not pursue a formal degree. Phelps suffers from ADHD and talks openly now about his depression and suicidal thoughts. My question: given that his mother was a school principal at that time – with all of her educational expertise – did she not realize or be aware of her son’s dilemma? Or was she one of those parents living vicariously through the success of their child as sport sociologists refer to this syndrome … driven by an ambition to see Michael finish his career as the ‘most ever decorated’ swimmer in the World? What about coach Bowman, worshipped by USA Swimming and ASCA? Was he only interested in the ‘swim machine’ Phelps to advance their common success – and not in Michael Phelps, the ‘human being,’ who needed desperate help? Did he not recognize the symptoms?

By Sally Jenkins

Washington Post

February 11, 2020

Modified by Schloder

Michael Phelps: “Olympians face greater Mental Health Risks”

…And Does the USOPC care?

One would think that athletes competing for the United States are better cared for these days. Not so! Not even after William Moreau in a lawsuit accusing the USA Olympic Committee officials of mishandling mental health issues. And especially, when Phelps is asked what the leadership response was to his revelation that he suffered from depression while winning all the Gold medals… "he was quiet for some time…" and that is the response I got from them! How long should I sit here and stay silent? … Because that is what I got… silence…nothing!” It is a system that continues to be profoundly distrusted by the very champions it is supposed to serve.

We also should remember the Larry Nassar sex scandal. Many female gymnasts still deal with mental health issues, which cause them to fear career repercussions if complaining or showing too many signs of mental distress (See April Newsletter-Series on Sexual Abuse). It is a system that for so long has existed on the commodification of young bodies that it became insensible to inner pain. It is also a system that has had trouble re-purposing itself, and still produces more propaganda than reform, still overpays all the wrong people at the expense of those who work the hardest. It is a system that remains a top-down operation with athletes at the bottom, fearful of speaking up. Katie Uhlaender (skeleton racer) states, “to be clear the only right we have is the right to compete.”

Moreau, Vice President of Sports Medicine for the USOC filed a retaliation lawsuit claiming he was wrongfully fired because he pressed too hard for athlete-health protection. Perhaps the most disturbing claim was that the USOC is not following standards of care related to the management of suicidal athletes and lacks the appropriate internal resources to deal with them. Moreau warned the USOC in March that an athlete might take their life – and shortly afterward Kelly Caitlin killed herself.

Michael Phelps about Michael Phelps

In the HBO documentary ‘The Weight of Gold’ Michael Phelps had this to say:

I put myself through a 4-year grind – debating if I should do that again

One event – one performance – and back to the grind for 4 more years

I got into drinking and I am a wreck – arrested again in 2014 – went into treatment for 45 days

I locked myself in a room for 4 days

I am extremely thankful that I did not take my life

A daily struggle

People say: ‘just get help’

No help for depression

It is a ‘game posturing’ – so, mental issues are not good – not mentally fit – for whatever reason, do not talk about it – is seen as weakness

From the outside, you have everything – but not inside

Seen just as the swimmer – not the person

They tore me down and built me back up

No one cared to help us

Leave it all behind – now what? – No program to help in that transition

Change perception of mental health – we are human beings

By Susan Scutti

CNN

January 20, 2018

Modified by Schloder

Michael Phelps: “I am extremely thankful that I did not take my life”

Far away from the pool, Phelps shared the story of his personal encounter with depression at a Mental Health Conference in Chicago during the week of January 20, 2018. “You do contemplate suicide,” he told the audience. He highlighted his battle against anxiety, depression, and suicidal thoughts. Asked what it takes to become a champion, he immediately replied: “that part is pretty easy… it is hard work, dedication, not giving up.” Phelps is known principally as the most decorated Olympian of all time, with a total of 28 medals spanning over four Olympic Games. He has actually competed in five Olympics but did not medal at his first Games in Sydney, Australia, in 2000. I wanted to come home with hardware, the feeling that helped him break his first World record at age 15 in 2001, and later earn his first Gold medal at the Athens Games in 2004. “I was always hungry, hungry, and I wanted more. I wanted to push myself to see what my max was.”

But intensity and perfectionism had their price! Phelps: “really, after every Olympics, I think I fell into a major state of depression” when asked to pinpoint when his trouble began. He noticed a pattern of emotion “that just wasn’t right at a certain time during every year around October or November, and that 2004 was probably the first depression spell I went through.” That was the same year that Phelps was charged with driving under the influence. And then there was the photo taken in Fall 2008, just weeks after he won eight gold medals at Beijing, that showed him smoking from a bong. He later called his behaviour “regrettable.” “Drugs were a way of running from “whatever it was I wanted to run from.” Phelps punctuated his wins at the Olympics in 2004, 2008, and 2012 with self-described “explosions.” He said, “he hit his lowest after the 2012 Olympics. He did not want to be alive anymore.” What that “all-time low” looked like was Phelps sitting alone for “three to four” days in his bedroom, not eating, barely sleeping, and “just not wanting to be alive,” he said. Finally, he knew he needed help.

…I remember going to treatment my very first day. I was shaking because I was nervous about the change that was coming up. I needed to figure out what was going on.” His first morning in treatment, a nurse woke him up at 6:00 am and said “look at the wall and tell me what you feel.” On the wall hung eight basic emotions, he recalled. “How do you think I feel right now, I’m pretty ticked off, I’m not happy, I’m not a morning person, he angrily told the nurse” (interesting … because swimmers have to get used to early morning work-outs. One reason I never had them in my private club, but was required to be on deck for varsity training).

…Once I began to talk about my feelings “life became easier.” I said to myself “why didn't I do it 10 years ago.” But I was not ready. I was very good at compartmentalizing things and stuffing things away that I didn’t want to talk about. I didn’t want to deal with it. I didn’t want to bring it up – I just never ever wanted to see those things…

Today, by sharing his experience he has the chance to reach people and save lives… and “that’s way more powerful. Those moments and those feelings and those emotions for me are light years better than winning the Olympic Gold medal,” he stated.

By Chris Murphy and Coy Wire

CNN

July 7, 2017

Modified by Schloder

Michael Phelps: “I locked myself in my room for four days”

For a man who glides so quickly through the water, it seems inhuman to think of confining himself to one room for four straight days. But such was the depth of a spiral that would threaten to cripple the comeback of one of the greatest swimmers of all time. His self-isolation followed a second charge of driving under the influence of alcohol in September 2014 that led to a six-month suspension by USA Swimming. Phelps told CNN, “I am so thankful for the support I have. Those days when I was sitting in my room, where I didn’t move for four days, I had the support team of my friends and family members.” Retiring after the 2012 Games, “his self-worth deserted him. He lost purpose and direction,” he said. He describes

…The darkness that enveloped him as “a time bomb waiting to go off.” It was during this period he even contemplated suicide. Asked what scared him most in his life, I would probably say when I didn’t want to be alive anymore. At that point, “I thought the best thing to do is just not be here. I’ve been known to not always make the best decisions. It has put me into interesting and tough spots at times…

While it took talent and determination to become the champion of all times, it also took courage to admit he needed help.

…I think it took those spots for me to be able to learn exactly what’s going on and what I needed to change. At that time I just knew I needed help and knew I needed to change something in my life. I was kind of in a lost place; so, we did some research on what we could do, and I went into treatment for a couple of weeks, and just basically rebuilt myself. They kind of tore me down and built me back up, and I went through some things that I never wanted to go through before…

Michael Phelps: Triumphant Rio Return

Phelps had been retired for two years before deciding to compete in Rio at the age of 32. With Rehab behind him and regaining his focus, he also rediscovered his zest for competition and got himself in better shape than he had ever been before. The desire for training that had, by his own admission, waned in the lead up to the 2012 Olympics, even though he earned six medals, four of them Gold.

…I knew I had to get myself in the best physical shape I could, especially at the age of 31. For me that was eating, sleeping right, doing every little ABC to make sure I was prepared for every single workout as I could. Eating became a job. There were days when you’re tired and you don’t want to eat but you have to, you’re forcing yourself to eat and it was just painful. I got down to four-and-a half percent body fat. I mean, it’s basically like skating on thin ice – any lower than that is unhealthy. Holy hell, that four-and-a half percent was just ridiculous. I don’t think I’ll ever get back to that again…

Michael Phelps: The Perfectionist

In his fourth Olympics, Phelps entered six events in Rio and won five. His tally of 28 medals sets him apart as the most decorated athlete of all time – 10 ahead of Russian gymnast Larisa Latynina. Though his triumphant returned thrilled sports-loving fans across the globe, the perfectionist Phelps can still pick a few holes in his performance. “The 200m Butterfly was something that I wanted back. I wanted to retire with that race Gold medal.” He had lost that event to South African Chad le Clos in 2012.

…I am always hard on myself. I mean, I saw the replay of the 200m Individual Medley this morning and they’re like it was amazing and I was like, Yeah, still did not break the world record. That was the one thing I wanted – I wanted to break one more world record. I wanted to go out with 40 world records (has 39) and that would have been awesome. But you know what, to four-peat that race is pretty awesome…

Michael Phelps: The Mental Health Ambassador

Phelps has implemented stress management offered by the Michael Phelps Foundation and works with the Boys and Girls Clubs of America. Today, he understands that

…It’s OK to be not OK and that mental illness has a stigma around it and that’s something we still deal with every day. I think people actually finally understand it is real. People are talking about it and I think this is the only way that it can change…

Speaking out is the turning point for Phelps in his post-swimming career. He is dedicated to encouraging others to seek help, especially children. He and fellow Olympian Allison Smith (swimming) were Ambassadors for the National Children’s Mental Health Awareness Day in May (2020).

…As an American it’s seen as weakness to ask for help and in our society. It’s just not what you do. It took me a while to get to a point where it’s OK to ask someone for help. When I went into treatment I didn’t want to talk to anybody. I did not open up, and two or three days into it, I was like I am here for 45 days. I might as well do this. I might as well just attack it. I looked at it as another challenge for me to get better. I just took full advantage of it, and dove in and this is where we are today…

When or if you watched in awe Michael Phelps’s performances throughout the years and especially at the Olympics would you have guessed the mental pain he endured? Stoically, he never showed it in front of the TV cameras. Oh, how many young swimmers idolized him or still do…wanting to be like him. Yes, but he paid ‘a hefty price as the human – the person Michael Phelps!’

Suicides Among High School and College Athletes

Athletes face pressures that can adversely affect mental health. Injuries, pressure to meet the expectations of fans, coaches, and teammates, and trying to balance athletics with academic commitments can all increase the risk of depression.

The latest Tragedies:

London Bruns (2007-2020) – High School Volleyball, died September 21 at age 13

Elise Kersch (2003-2020) – High School Volleyball, died October 4, at age 17

Kelly Catlin (1995-2019) – pursuit racing cyclist; silver medal at the 2016 Olympic games; 3 consecutive World championships between 2016-2018; died in her dorm at Stanford University March 7, 2019

Ian Miskelley (2000-2020) – swimmer committed suicide September 17, 2020, two weeks shy of his 20th birthday; he was a USA junior national medalist and qualified for U.S. nationals in 2017; current member of the University of Michigan men’s swim team and two-time Academic All-Big Ten honours

Dr. David Geier (2015, May 20), an orthopaedic surgeon and sports medicine specialist in Charleston, South Carolina reported that the mental health of college students has been getting more attention after football player and wrestler at Ohio State, Kosta Karageorge killed himself on November 30, 2014, at age 22. He was reported missing by his mother, other family, and friends after they had received distressing text messages and social media posts concerning his headaches around a recent concussion. He proceeded to miss upcoming football practices and finally the Ohio State game against rival University of Michigan, raising concerns about his welfare. Following a dispute with his girlfriend on November 30, 2014. Karageorge climbed in a dumpster near his apartment and shot himself.

According to statistics, suicide is the second leading cause of death in college students – athletes and non-athletes. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports an incidence rate of 7.5 suicides for every 100,000 college students.

Statistics, May 20, 2015 (Geier, 2015):

35 suicides, including 6 cases of suspected suicide, occurred among student-athletes over a nine-year period

477 athletes died from all causes during that time

Suicides presented 7.3% of all deaths; was the fourth most common cause of death after accidents, cardiovascular fatalities, and homicide

29 of the 35 suicides (82.9%) were male athletes

In terms of sport, football players made up the highest number of suicides (13 of 35); Soccer had 5; Cross Country and Track 5; Baseball 4; Swimming 3

Attempts or Suicides Among Professional Athletes

It is always heartbreaking to find out that there are numerous athletes, who have ended their lives because of depression or substance abuse due to injuries, concussions, alcohol, and painkillers. “20 Athletes Who Sadly Committed Suicide” relays the story of 20 professional athletes in boxing, football, hockey retrieved from https://www.thesportster.com/entertainment/20-athletes-who-sadly-committed-suicide/

Many athletes especially football, hockey and boxing are suffering from CTE (chronic traumatic encephalopathy) which impacts behaviour and is linked closely in a number of deaths.

Some examples:

Kid McCoy (1872-1940) – ended his life on April 18, 1940, by taking sleeping pills at age 67

Robert Enke (1977-2009) – German professional soccer player (goalkeeper); committed suicide on November 2009; was widely considered to be a leading contender for the German #1 spot at the 2010 World Cup; standing in front of a regional express train at a level crossing, he jumped into the oncoming train; police confirmed a suicide note was discovered; his widow revealed that he had been suffering from depression for six years and was treated by a psychiatrist after the death of his daughter Lara in 2006; he struggled to cope with her loss

Kenny McKinley (1987-2010) – NFL Denver Broncos; died of a gunshot wound at age 23

Rick Rypien (1984-2011) – NHL Hockey Vancouver Canucks; struggled with clinical depression for most of his life; died on August 15, 2011, at age 27

Wade Belak (1976-2011) – NHL Hockey with five different NHL teams before retiring after the 2010-11 season; sent down to the AHL; had arthritis in his pelvis; accepted a job in the front office; two months into the offseason was found dead

Derek Boogaard (1982-2011) – aka “The Boogeyman”; NHL Hockey Minnesota Wild and New York Rangers; died of a drug overdose at age 28; known to be suffering from CTE and depression

Junior Seau (1969-2012) – NFL linebacker San Diego Chargers and Miami Dolphins; shot himself in the chest at age 43 on May 2, 2012

Jovan Belcher (1987-2012) – NFL Kansas City Chiefs; shot and slew his girlfriend, mother of his child, on December 1, 2012; drove to Kansas City Chiefs' practice facility and shot himself

Greg Johnson (1971-2019) – NHL Hockey with four different teams; found dead by his wife in their basement; left behind two daughters

Leon McKenzie (1978-) – former English soccer player; played as a forward from 1995 to 2013; scored in all four English professional leagues during his career; in 2009, while playing for third-tier Charlton Athletic; decided to try to kill himself by overdosing on pills in his hotel room; was found; turned instead to boxing as a professional boxer, competed in the super middleweight class

The Current Crisis: A Reflection

Why does it take a pandemic to finally come to the realization that a suicide crisis actually exists and has for many years? One has to question why so little attention was paid to the time when the first cases were reported and teenage suicides started to increase. For example, suicide rates among girls, ages of 15-19, reached a 40-year high in 2015, according to the National Center for Health Statistics (Susan Scottie, August 3, 2017, CNN). The rate for those girls had actually doubled between 2015 and 2017, according to research. In January 2017, a 15-year old freshman at a High school in Ohio took his life becoming the sixth teenage student from that same school district to kill himself within a six-month period! Three of those suicides occurred in a span of 11 days in January. So, where were the responsible school authorities, teachers, counsellors, and/or parents?

CNN UK reports that the biggest killer in the UK is suicide for men under 45. One person takes their life every 90 minutes – the same amount of time it takes to play a soccer match. We can safely assume the same or similar pattern is found among youth in the USA. Could one argue that the start-up of Facebook in February 2004 might have had an impact on young and older people? They are drawn to this ‘tech tyranny tool’ to make social friends and find social acceptance but also receive social rejection. Nowadays, driven by daily media and varying medical reports, fear, anxiety and depression related to the Pandemic is amplified as the number of individuals suffering from mental illness around the world continues to grow. Characterized by what people experience in their minds but sometimes involving physical symptoms and their emotional well-being, the true cause of many mental health disorders is yet to be discovered although numerous symptoms are scientifically understood.

It has become very apparent that society has been failing people of all ages for some time as both Canada and the USA experience a nation-wide crisis due to the high use of opioids and other pharmaceutical drugs. David Parker (Calgary Herald, October 12, 2020) reports that mental health issues are on an alarming rise among young people in Canada with far too many struggling with conditions such as anxiety, depression, eating disorders, and schizophrenia. A recent poll found that over half of students returning to school feel disconnected and unsupported by their school. Albeit, athletes are students and vice versa many students are athletes. It is a major concern because there is a strong connection between mental health, academic and sport performance. Albeit, athletes are students or vice versa students are athletes. This becomes a major concern because there is a strong connection between mental health, academic and sport performance. Mental health is critical in order to navigate one’s well-being (p. A7). Brae Anne McArthur, a clinical psychologist and postdoctoral fellow at the University of Calgary writes: “Crisis threatens young psyches” (The Calgary Herald November 30, 2020, p. A4).

…The tween and teenage range is really crucial for the development of mental health disorders; so, this is a time when we see an escalation in a lot of symptoms, depression, anxiety, and suicidal rates. Ultimately, how they manage and cope now is predictive of their adult mental health…

Christopher Primeau (2020) states,

…Experts already are noting a spike in a wide range of mental issues and self-harming behaviour across Alberta (Canada). Statistics show that half of all those who develop health disorders experience symptoms in their early youth. Alberta has the second highest suicide rate in Canada, and youth are the most affected. In 2018, nearly 600 children under the age of 14 were admitted to the hospital after a suicide attempts (October 5, The Calgary Herald, p. A8)…

John Ivison, (2020) reports that the number of Canadians, who stated that they have ‘strong mental health’ has fallen 23% from 67% to 44% as of last October. Canada Suicide Prevention reports an upsurge in calls with a 200% increase between October 2019 and the prior year. Deterioration of mental health among the nation’s young people is no surprise. University students have no structure, no schedule, no social life. Students in secondary schools see their ‘wonder’ years gone by. Even before COVID, there was an emerging mental health crisis facing young Canadians. One in five experienced mental health disorder, according to the Canadian Institute for Health Information. In the period 2018-2019, emergency department visits and hospitalizations among young people for mental health disorders rose 60% while hospitalizations for other conditions fell 26%. One in 11 young people were dispensed anxiety or anti-psychotic medication in 2018-2019 (The Calgary Herald, National Post, pp. NP1, NP3). Although given these statistics, we do not have the number of young or elite athletes, who might have experienced anxiety, depression or suicidal thoughts during 2018-2019 periods or during the current Pandemic.

Pop Culture and ‘Hyped’ Body Images

The Social Signal: Hide Your Emotions because Boys Don’t Cry!

Could our culture and the conundrum about modern-day body images potentially have a big influence? Young people’s perception and self-identification are distorted by continuous ‘bombardment’ and daily Media displays on TV and fashion magazine covers. Athletes at all levels, male and female, have to deal on one hand with that exposure while conversely don’t feel comfortable enough to discuss or disclose their body or health issues with their coaches, such as alcoholism, drug use, addiction, anxiety, depression, suicidal thoughts or female menses, bulimia, and anorexia. And could society endorse the traditional myth that boys need to be tough; do not cry… therefore, have to be strong and ‘suck it up or don’t be a wussy’ because only girls cry… be linked to current mental health issues? Besides, boys or male athletes are said to be very uneasy to ‘open up from man to man’ about any emotional or psychological issue (See Phelps). It is well established that men loathe sharing their innermost conflicts because letting emotions become visible or known is interpreted as a sign of weakness! Such lack of trust in their athletic environment and personal apprehension might very well play a big part (See Phelps).

Leon McKenzie, a former Professional Soccer player in the UK (see athletes and suicide), with an injury-prone career, tried to commit suicide in a hotel room in 2009. He recalled the hamstring strain he suffered, which tipped him over the edge, and describes the pain he felt as ‘someone taking my heart out of my chest. He believes that the “stigma surrounding judgement of people with mental health and men’s pride are the biggest obstacles in combating high suicide rates.” He remembers for the first time, thinking:

…I actually want to kill myself. I went back into the treatment room, sat down on the bed and burst into tears and cried. I don’t think people really speak to someone they might see crying, especially a man. I have been very open about trying to take my life. That led to me, fortunately, waking up in the hospital and having another chance at life…

What About Coaches and Their Role?

It is maintained that the task of sport coaches is to ensure a) young athletes have FUN, b) strive to become more successful, c) desire to move on to higher levels, d) engage in sport with a healthy mental state and outlook, and e) ultimately stay active and happy later on in life. In 1976, former swimmer and swim coach Philip Scott (1976, pp. 17-19) wrote that the essence of coaching is to help swimmers discover their pathways. It is that kind of education that young athletes most desperately need – to be turned on to life, excited by its possibilities, and to become ecstatic in their realization; to feel good about themselves and to be confident in their abilities to use their body and mind to meet whatever challenges. If nothing else, we should encourage young athletes to entertain this awareness because it becomes worthwhile in terms of their lives as a whole. What we want them to have as fully developed persons we must begin to show them early on. At its best, sport can provide an ideal medium for doing just that.

Let’s define our Profession:

…A calling requiring specialized knowledge and long and intensive preparation including instructions in skills and methods as well as in the scientific historical or scholarly principles underlying such skills and methods; maintaining by force of organization or concerted opinion high standards of achievement and conduct (Webster’s Third New International Dictionary)…

Based on this definition, most coaches are very successful in advancing athletic success with a high focus on developing physical and athletic abilities, refining skills and techniques, planning racing strategy, and incorporating mental training to improve performance. But something is amiss in this undertaking! Few coaches feel comfortable or speak directly and openly with athletes about their personal perception and dealings with the body-mind-sport connection (how athletes see themselves and how they feel about themselves).

The current staggering increase of mental health issues in society and recent statistics point to the fact that 25% of young people 18-24 suffer from mental problems. Sport sociologists propose that any societal issue is reflected about 10% in sports. Therefore, present-day coaching responsibilities and accountabilities have to be re-assessed – in my opinion – and whether or not coaches are actually trained and capable enough to deal with such challenges. It appears that many lack the training and expertise to provide such support. How do coaches learn to identify such adversity like anxiety, depression, eating disorders, or suicidal tendencies?

John O’Sullivan of “Changing the Game” had this to say about young athletes during the current Pandemic (November 18, 2020 Newsletter, modified by Schloder):

…I want to talk about the mental health of our athletes right now. For many kids, this month brings a close to their fall sports season. Since many winter sports shut down (wrestling, basketball, etc.) many athletes may be experiencing more social isolation than ever before. Parents have told me that if it were not for sports this summer and fall, their child would have really been struggling. University of Wisconsin study in May found that 65% of young athletes were experiencing anxiety symptoms, and 68% were experiencing depression. Physical activity levels had dropped 50% at the same time…

Awareness and Understanding of the Individual and Gender Differences

Think about the way you coach because personal perceptions create certain barriers. For example, do you notice or even know the way you affect your athletes, males or females? This is not only vital during the growth and development phase when emotions tend to be unstable. It also applies to elite athletes because many become stressed out and depressed about their training or lack of progress. Performance issues can be linked to physical, medical, potential burnout, or mental breakdown, and mental health factors. Moreover, do you understand gender differences because they are fundamental to maintain a positive and healthy coach-athlete relationship? Female menarche is correlated to hormonal changes in the monthly cycle affecting performance. Seventeen percent of body fat is required for menarche to be maintained and 22% to restore menstruation (Neinstein, Katzman, Callahan, Gorden, Joffe, & Vaughn, 2016). It is a critical factor to recognize eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa or bulimia. Do you know how to spot any of these syndromes, which are psychological in nature related to low self-esteem and self-image?

Moreover, female athletes tend to be more ‘emotionally strung’ during puberty and pre-menstrual days; they cry when complemented and cry when one corrects their performance … and often they don't even know the reason they cry or ‘feel down!’ They just do! I am quite sure you have experienced such scenarios. It is essential to be more cognizant and sensitive toward athletes’ daily feelings, emotional state and displays, lack of communication, and interaction with you and teammates. Foremost, greater support and empathy is needed from you, not just your interest in their performance. And let us not forget that coaches have to ‘earn athletes’ respect’ for a solid, healthy, and trustworthy relationship and not automatically assume it exists!

Maybe it is a gender ‘thing’ – ‘mother Nature’ has provided women with a certain female ‘psyche’ combined with somewhat greater compassion (little boy gets hurt… usually runs to mother for comfort, not father), greater awareness, and often more understanding. It requires the ability to observe body language, being aware of mood changes, recognizing gestures, and facial expressions. How do you determine if today’s session is going to be productive or just ‘another one of those lousy practices? Or is something else bothering the athlete or are they just not feeling well?’ Are they ‘bubbling and full of energy or move ‘slower than molasses?’ Are they taking their time to get into the workout mood or is there a physical or a mental issue? How do you know and assess this? When athletes enter competitive events your prior assessment should be whether or not they are physically, psychologically, and mentally really up to the task and/or the expectations as the state of wellness and emotional maturity is a decisive factor. Are they ‘absolutely ready’ or are you the only one that thinks so? In the end, the perception of personal efficacy [I can do this], skill competence [I completely possess and have this skill under control], and subsequent self-esteem make the difference for performance readiness based on a ‘sound’ competitive and a healthy mindset.

Acting in the role of advisors, counsellors, or mentors coaches are very influential during the transition from childhood to early adolescence since young athletes look for role models, guidance, and understanding. However, some caution is heeded here because coaches are leaders not ‘buddies to win popularity contests.’ Patterns of behaviour and lifestyle choices are established during early adolescence, which can affect both current and future health and well-being (See Michael Phelps). Athletes may struggle during this time to adopt healthier lifestyle habits (‘healthy nutritious’ versus ‘fast’ food habits), said to decrease the risk of developing chronic diseases later on in adulthood. They learn to avoid the use of tobacco, cannabis, or vaping, which are currently on the rise among the young due to social and/or peer pressures.

Athletes Lost Within the Confusion Of The Body-Mind-Sport Connection

Doing Sport Versus ‘Soul-making’ of Sport

It is particularly discouraging that only academia seems to be studying the body-mind sport-connection from an intellectual perspective because the general public doesn’t think about it and most coaches are not the least concerned with ‘that stuff.’ Well known German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche [1844-1900] stated, “We think with our body through internal processes: “We think – We feel – and therefore…we will.” Of course, that was the belief held before modern sport science took to the main stage and began to smother thoughts on the ‘essence or human totality’ by turning athletes into ‘human performance machines’ because sport itself had become a quest for record performances at any cost as stated by Hoberman (1992), who examines the deep connections between culture and the cult of high-performance sport. The traditional focus has always been on ‘playing or doing sports’, which is not the same as learning about one’s body through or via sport [knowledge of body]. Well-known sport psychologists refer to a certain phenomenon in sport called ‘flow,’ a psychological dimension because it should be part of the athlete’s ‘harmonious interaction between body and movement’ – the so-called ‘soul-making’ in sport. For example, moving like robots several hours ‘day in and day out’ or up and down the pool lane does not represent a well-balanced interaction between body and activity.

Elite athletes nowadays are frequently treated as ‘human performance machines’… as someone stated:

…To be chiseled, tuned, piped, and drilled’ rather than having essence…

…Prune it like a garden, walk it like a pet, keep it neat and trim and odor-free, and control it…

As a result, they are uneasy to debate the body-sport connection. I had baffling reactions – to say the least – by elite performers as some got annoyed, some got absolutely silly, and some thought ‘I was nuts!’ This raises some interesting queries and concerns. How are athletes going to know and understand themselves or even figure out when body cognizance, awareness and emotional states are never addressed? How are coaches supposedly dealing with athletes’ ‘inner psyche’ when they themselves lack interest, the education and/or specific training, and are only interested in creating the ‘success’ machine?

The understanding of the intricate ‘body-mind-sport connection’ means being ‘in-tune with ones-self’ and is paramount for achieving success at any athletic level. The absence or lack thereof is unfortunate because it is central for (a) physical and especially mental wellness; (b) successfully managing daily living skills; (c) maintaining overall wellness and life quality; (d) avoiding physical breakdown, burnout, or injuries; and (e) striving to produce and maintain consistent winning performances (Schloder, 1998).

Definitions:

Mental Health:

A person’s condition– with regard to their psychological and emotional well-being, dealing with "pressure seemingly affecting their mental health." Mental health is important at every stage of life, from childhood and adolescence through adulthood. Many factors may contribute to a person’s mental health issues. It includes the emotional, psychological, and social well-being affecting the way they think, feel, and act. It also helps determine how they handle stress, relate to others, and make choices. Over the course of their life, if people experience mental health problems, thinking, mood and behaviour are affected.

Mental Well-being:

Mental wellbeing– the way one responds to life’s ups and downs. It has a deeper meaning with implication for our lives because it includes the way we think, handle emotion (emotional wellness), and act is an important part of who we are.

Depression:

Impacting an estimated 300 million people, depression is the most common mental disorder and generally affects women more often than men. It is often characterized by loss of interest or pleasure, general sadness, feelings of guilt or low self-worth, difficulty falling asleep, eating pattern changes, exhaustion and lack of concentration. Depression doesn’t just arise as a result of ‘too much or too few’ brain chemicals, specifically serotonin, as it is often depicted. Rather, several forces such as genetics, life events, medical problems and medications can bring the illness on. Since depression can be both long-lasting or recurring, it can severely interfere with a person’s ability to function at work or school and can have a negative impact on relationships. At its most severe state, depression can lead to suicidal thoughts and actions. To effectively treat depression in some cases, cognitive behaviour therapy, psychotherapy and antidepressant medication can be valuable.

Anxiety:

It is not uncommon for a person experiencing depression to also have anxiety (and vice versa), a disorder that affects 40 million adults in the U.S., or 18.1 percent of the population, every year. Anxiety disorders develop from a multitude of factors, including genetics, brain chemistry, and life events, and while it is a highly treatable illness, only 36.9 percent of those who live with anxiety actually seek out treatment, and ultimately, access it. Psychotherapy and medication play an important role in helping to control and manage the symptoms of anxiety.

Bipolar Affective Disorder:

Engendering both manic and depressive episodes, sometimes book-ended, and sometimes featuring moments of “normal” or stabilized mood, this illness impacts approximately 60 million people worldwide. Manic episodes can contain elevated or irritable mood, hyperactivity, inflated self-esteem and a lack of desire to sleep.

Hypomania:

A less severe form of mania – depressive episodes is often characterized by feelings of extreme sadness, hopelessness, little energy, and trouble sleeping. While the cause of bipolar is not entirely known, a mixture of genetic, neurochemical and environmental factors can play a role in the progression of the illness, which can be treated through medication and psychosocial support.

Schizophrenia and other Psychoses:

Psychoses, including schizophrenia, are severe mental illnesses impacting about 23 million people worldwide and are characterized by distortions in thinking, perception, emotions, sense of self, and behaviour. Those who have these illnesses can experience hallucinations and delusions starting in late adolescence or early adulthood, making it difficult for people to work, study, or interact socially. Due to stigma and discrimination, many who experience these mental illnesses do not have access to adequate health and social support (sometimes leading to housing insecurity), which could help treat the disorder.

Mental health illnesses are a global issue that touches nearly every person in some way – and these are just a few of the most commonly documented. While every situation is unique, there are treatment and recovery options available to help an individual achieve strength and support. Taking the time to recognize your symptoms and get an accurate diagnosis can help best determine the most appropriate treatment – be it pharmaceutical intervention or a treatment plan involving psychotherapy with a licensed therapist.

Detecting Early Warning Signs

Maybe you or someone you know is living with mental health problems, and who is experiencing one or more of the following feelings or behaviours can be an early warning sign of a problem:

Eating or sleeping too much or too little

Pulling away from people and usual activities

Having low or no energy

Feeling numb or like nothing matters

Having unexplained aches and pains

Feeling helpless or hopeless

Smoking, drinking or using drugs more than usual

Feeling unusually confused, forgetful, on edge, angry, upset, worried, or scared

Yelling or fighting with family and friends

Experiencing severe mood swings that cause problems in relationships

Having persistent thoughts and memories you can't get out of your head

Hearing voices or believing things that are not true

Thinking of harming yourself or others

Inability to perform daily tasks like taking care of your kids or getting to work or school

Where Do We Go From Here? …

So… the Story goes:

…One day Alice came to a fork in the road and saw a Cheshire cat in a tree…

Which road do I take? She asked

Where do you want to go – was his response

I don’t know, Alice answered

Then, said the cat, it doesn’t matter (Lewis Carroll – Alice in Wonderland)

Recommendations

Based on the rising mental health issues among athletes, the body in sport and athletes’ mental well-being has to become part of the new coaching portfolio. While there are National Helplines for suicides listed for both Canada and the USA, the question is – in my mind – how well are these people trained to understand the specific and unique portfolio of an individual sport and team sport athletes?

Some in the coaching community started to intermingle philosophical inquiry during the 1990s with their technique training to “endow” elite athletes with that “awesome body in-tune-ness” What’s wrong with that? Nothing – except possessing “in-tune-ness” does not happen by “osmosis or overnight” or because some leading figure says so!

Sport communities at large could greatly benefit from offering specific training seminars and courses in the body-mind-soul-spirit-sport connection, recognizing symptoms, and dealing with mental health issues

Coaches need to incorporate the body-mind-health concept in their training, not just talk, hear, write, or philosophize about it in conferences. The whole process goes far beyond! It is one of educating athletes early on.

Incorporate Progressive Relaxation, Meditation, and Yoga in sports programs to assist young athletes in becoming more aware of body tension, anxiety, fears, and depression

If that is the case, then coaches have to become more serious and thoughtful about athletes’ mental health and seek training in those areas

Older and elite athletes need to be encouraged to take initiative and be more knowledgeable about their body and not just ‘jump on the bandwagon’ because it is cool, trendy or fashionable!

Then coaches need to work on One-on-One mentoring to help athletes navigate through adversity

As well-known swim coach Cecil Colwin stated in a 1994 conference, “more non-conformists or iconoclasts in the North American swimming world are needed but they are not easily accepted in those circles!”

National Suicide Hotline Canada: 833-456-4566

National Suicide Hotline USA: The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline can be reached at 1-800-273-8255, and the use of 988 was approved

Michael Phelps Foundation: https://michaelphelpsfoundation.org/

References:

Bharadwai (December 16, 2020). As suicides rock local sports communities, concerns grow over athletes’ mental health. Retrieved December 19, 2020, from https://washingtonsources.org/entertainment/sports/as-teen-suicides-rock-local-sports-communities-concerns-grow-over-athletes-mental-health/103702/

Boren, C. (2020, May 11). U.S. Olympic bobsledder Pavle Jovanovic dies by suicide at 43. The Washington Post. Retrieved December 14, 2020, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/sports/2020/05/11/us-olympic-bobsledder-pavle-jovanovic-dies-by-suicide-age-43/

Cardenas, F. (2020, October 15). For youth soccer players, COVID-19 has had dire mental health consequences. The Athletic. Retrieved November 30, 2020, from https://theathletic.com/214072140745/2020/10/15/youth-soccer-covid-19-mental-health-ecnl/

Dutton, J. (2020, May 18). Additude. Retrieved September 18, 2020, from https://www.additudemag.com/michael-phelps-adhd-advice-from-the-olympians-mom/

EDUInReview.com. Retrieved September 18, 2020, from https://www.eduinreview.com/blog/2012/08/michael-phelps-attended-university-of-michigan-while-training-for-the-olympics/

Geier, D. (2015, May 15). How common are suicides in college athletes? Retrieved December 7, 2020, from https://www.drdavidgeier.com/suicide-college-athletes-how-common/

Green, S. (2020, October 9). Volleyball community mourns the loss of two young women. Prepvolleyball.com Retrieved December 19, from https://prepvolleyball.com/articles/high-school/volleyball-and-society/389582https://prepvolleyball.com/articles/volleyball-community-mourns-the-loss-of-two-young-women/428500

Grez, M. (2018, January 18). Inside the mind of a suicidal sports star: I wanted 'to kill myself,’ recalls Leon McKenzie. CNN. Retrieved December 4, 2020, from https://cnn.com/2020/01/18/sport/football-suicide-blue-monday-leon-mckenzie/index.html

Hamilton, A. (2019). Mental illness in athletes: The most hidden injury. Part 1. Peak Performance, March 3, 2019. Guildford, UK: Green Star Media.

Hamilton, A. (2019). Mental illness in athletes: The best way forward to brighter times. Part 2. Peak Performance (n.d.). Free Issue. Guildford, UK: Green Star Media.

Hari, J. (2018). Lost connections. Uncovering the real causes of depression – and the unexpected solutions. NY: Bloomsbury.

Hoberman, J.M. (1992). Mortal engines: The science of performance and the dehumanization of sport. Caldwell, NJ: Blackburn Press.

Ivison, J. (2020, December 10). The other COVID crisis. Pandemic taking toll on mental health. The Calgary Herald and National Post, pp. NP 1, 3.

Jenkins, S. (2020, February 11). Michael Phelps says Olympians face greater mental health risks. Does the USOPC care? The Washington Post. Olympic Perspective. Retrieved November 15, 2020, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/sports/olympics/michael-phelps-says-olympians-face-greater-mental-health-risks-does-the-usopc-care/2020/02/11/72afec9c-4ce9-11ea-b721-9f4cdc 90bc1c_story.html

Kane, A. (2020, September 28). A father speaks out after his son, a Michigan swimmer, takes his own life. Retrieved December 10, 2020, from Retrieved December 10, 2020, from https://www.newsbreak.com/news/2071325620921/a-father-speaks-out-after-his-son-a-michigan-swimmer-takes-his-own-life

Lail, G. (2020, September 16). One-on-One mentoring helps youth navigate stressful adversity. Resiliency is a skill that can be taught. Calgary, Alberta, Canada: The Calgary Herald, p. A11.

*Note: Gurpreet Lail is president and CEO of Big Brothers – Big Sisters of Calgary and area.

Lee, J. R., & Lee, B. (2000). Bruce Lee: The celebrated life of the golden dragon. Boston: Rutland.

Lester, D. (2011). Mind, body, and sport. Suicidal tendencies. An excerpt from the Sport Science

Institute’s guide to understanding and supporting student-athlete wellness. Retrieved December 8, 2020, from http://www.ncaa.org/sport-science-institute/mind-body-and-sport-suicidal-tendencies. NCAA.

Lester, D. (2011). Understanding and preventing College student suicide. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas.

Lester, D. (2012). Suicide in Professional and Amateur athletes. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas.

McArthur, B, A. (2020, November 30). Crisis threatens young psyches. The Calgary Herald, p. A4.

MentalHealth.gov. Retrieved October 5, 2020, from https://www.mentalhealth.gov/basics/what-is-mental-health

Miskelley, S. (2020, September 28). A father speaks out. Retrieved, November 15, 2020, from https://www.mlive.com/sports/2020/09/a-father-speaks-outafter-his-son-a-michigan-swimmer-takes-his own-life.html

Murphy, C., & Wire, C. (2017, July 7). Michael Phelps: 'I locked myself in my room for four days.' Retrieved November 15, 2020, from https://www.cnn.com/2017/07/03/sport/olympics-michael-phelps-swimming-mental-health/index.html

Neinstein, LS., Katzman, DK., Callahan, T., Gorden, CM., Joffe, A., & Vaughn, R. (2016). Neinstein’s adolescent and young adult health care (6th ed.). Alphen aan den Rijn, Netherlands: Wolters Kluwer Books. Retrieved September 18, 2020, from https://www.amazon.com/Neinsteins-Adolescent-Young-Adult-Health/dp/1451190085/ref=sr_1_1?dchild=1&keywords=Neinstein%E2%80%99s+adolescent+and+young+adult+health+care+6th+edition&qid=1609298302&sr=8-1

O’Sullivan, J. (2020, November 18). Impermanence and change. I want to talk about mental health of our athletes. Bend, OR: Changing The Game Project.

Parker, D. (2020, October 12). Centre for youth mental health will be a national leader. The Calgary Herald, p. A7.

Primeau, C. (2020, October, 5). Youth facing perfect mental storm. The Calgary Herald, p. A8.

Purcell, R., Gwyther, K., & Rice, SM. (2019). Health in elite athletes: Increased awareness requires an early intervention framework to respond to athlete needs. Sports Medicine, Open Vol.5 (Article 46). Open 5, 46 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-019-0220-1

Rapkin, B. (2020, July 29). The weight of gold. HBO Documentary. Brett Rapkin, Director. Production Company: Podium Pictures. Narrator: Michael Phelps.

Rapkin, B. (2020, August 4). Olympic athletes are dying:’ Doc sheds light on suicide among Olympians. The Associated Press.

Rao, A., Asif, IM., Drezner. JA., Toresdahl, BG., & Harmon, KG. (2015). Suicide in National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA): A 9-year analysis of the NCAA resolutions database. Sport Health: A multidisciplinary approach. Published May 20, 2015.

Scott, P. (1976). Aesthetics, education, and the aim of age group swimming. Los Angeles: Swimming World. November 1976, pp.17-19.

Scutti, S. (2018, January 20). Michael Phelps I am extremely thankful that I did not take my life. CNN. Retrieved November 30, 2020, from https://www.cnn.com/2018/01/19/health/michael-phelps-depression/index.html

Schloder, M.E. (1993-2006). Lecture Notes KNES 331-Foundations of Coaching. Calgary, Alberta, Canada: University of Calgary, Department of Kinesiology.

Shvartz, E. (1967). Nietzsche: A philosopher of fitness. Quest, 8(1), 83-89.

Stubbs, R. (2020, December 16). As tee suicides rock local sports communities, concerns grow over athletes’ mental health. The Washington Post. Retrieved December 17, 2020, from https://www.benningtonbanner.com/wapo/national/as-teen-suicides-rock-local-sports-communities-concerns-grow-over-athletes-mental-health/article_d06a855c-3fd9-11eb-b6da-0b829d7b9f9a.html

Sullivan, J. (2020, November 11). Protecting the mental health of our athletes. Blog.

Swift, N. (2016, May 13). The rise and fall of Michael Phelps. Retrieved, September 19, 2020, from https://www.nickiswift.com/14332/rise-fall-michael-phelps/

Retrieved October 3, 2020, www.hbo.com/documentaries/the-weight-of-gold

*Note: “The Weight of Gold” – HBO Sports documentary exploring the mental health challenges that Olympic athletes often face. The film is released during the time when the COVID-19 pandemic has postponed the 2020 Tokyo Games – the first time in Olympic history – and greatly exacerbated mental health issues. The film seeks to inspire discussion about mental health issues, encourage people to seek help, and highlight the need for readily available support.

Director: Brett Rapkin; Executive Producers: Brett Rapkin, Peter Carlisle, Michael O’Hara Lynch, Michael Phelps, Peter Nelson, Bentley Weiner, Jeremy Bloom, Amber Theoharis

Producer: Ellen Vanderwyden; Written: Brett Rapkin, Aaron Cohen

Retrieved October 5, 2020, from https://ca.search.yahoo.com/yhs/search?hspart=iba&vm=r&hsimp=yhs-&type=oaff_8804_FFW_US&p=Definition+of+mental health

Retrieved October 5, 2020, fromhttps://www.alltop10list.com/top-10-list-of-most-popular-mental-disorders/

Retrieved October 5, 2020, from https://www.nickiswift.com/14332/rise-fall-michael-phelps/

Retrieved November 20, 2020, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/sports/olympics/michael-phelps-says-olympians-face-greater-mental-health-risks-does-the-usopc-care/2020/02/11care/ 2020/02/11/72afec9c-4ce9-11ea-b721-9f4cdc90bc1c_story.html

Retrieved November 15, 2020, from https://1996+survey+Sports+Illustrated+and+parents+and+aggreeing+to+drug+use+by+their+children

Retrieved November 20, 2020, from https://www.cnn.com/2018/01/19/health/michael-phelps-depression/index.html

Retrieved November 30, 2020, from https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1226739/German-goalkeeper-Robert-Enke-dies-aged-32-suspected-suicide.html

Retrieved December 5, 2020, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LROU7SyQtUY

Retrieved December 5, 2020, from https://www.drdavidgeier.com/suicide-college-athletes-how-common/

Retrieved December 5, 2020, from https://www.talkspace.com/blog/the-top-five-most-common-mental-illnesses/

Retrieved December 5, 2020, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LROU7SyQtUY

Retrieved December 5, 2020, from https://www.drdavidgeier.com/suicide-college-athletes-how-common/

Retrieved December 5, 2020, from https://www.talkspace.com/blog/the-top-five-most-common-mental-illnesses/

Retrieved December 8, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kosta_Karageorge

Retrieved December 8, 2020, from https://www.thesportster.com/entertainment/20-athletes-who-sadly-committed-suicide/

Retrieved December 18, 2020, from https://www.ranker.com/list/athletes-who-committed-suicide/ people-in-sports

Retrieved December 18, 2020, from https://www.thesportster.com/entertainment/20-athletes-who-sadly-committed-suicide/

The Ann Arbor News

September 28, 2020

Retrieved December 10, 2020, from https://www.newsbreak.com/news/2071325620921/a-father-speaks-out-after-his-son-a-michigan-swimmer-takes-his-own-life

Andrew Kane

September 28, 2020

A father speaks out after his son, a Michigan swimmer takes his own life

Ian Miskelley, shown here during a race on March 10, 2018, was a star swimmer at Holland Christian before joining the swim team at the University of Michigan

Steve Miskelley wants to talk about an unspeakable tragedy. He is willing to get on the phone with a stranger to discuss, in detail, the worst thing that can happen to a parent. Doing so, he hopes, will help you or your child or your neighbour or your teammate.

Steve’s son, Ian, died by suicide this month. Ian was entering his junior year at Michigan, where he was a member of the swim team. To an outsider, Ian had so much going for him. “You wouldn’t know there was this demon lurking under the surface,” Steve says. When Ian was 11 years old, he realized something wasn’t right in his head. “Dad, I don’t know what’s going on,” Steve recalls him saying. “I just feel angry all the time.” Medical professionals determined Ian had anxiety brought about by depression. By the time he was a teenager he was on medication and had regular visits with psychiatrists and therapists. “It was an ongoing struggle,” Steve says.

For a time, Ian was cutting himself as a means to cope with the mental pain. That led to increased therapy visits, more careful monitoring of his medication. All the while, Ian was ascending the ranks as a youth swimmer in Holland, Michigan. He started swimming at age 7. By age 10, he was part of USA Swimming and two-time state champion. Ian traveled all over the country for meets. Colleges showed interest midway through his high school career. He visited several top programs and chose Michigan, a national power.

Steve and his wife, Jill, were relieved their son picked a school just 160 miles away. “It was within reach if something happened,” Steve says. Proximity alone didn’t ease their minds. They trusted Michigan’s resources: the counselors, psychiatrists, and world-class medical facilities. “The other schools we visited -- none of them gave any thought to (mental health),” Steve says. “It wasn’t even on their damn radar. Michigan is way ahead of the curve there.” Sure enough, Ian had a strong support team on campus. His personal psychiatrist was the director of psychiatric emergency service at the university hospital. Ian also saw a therapist in the athletic department. Josh White, the swim team’s associate head coach, “took a personal interest in Ian and stayed very close to him,” Steve says.